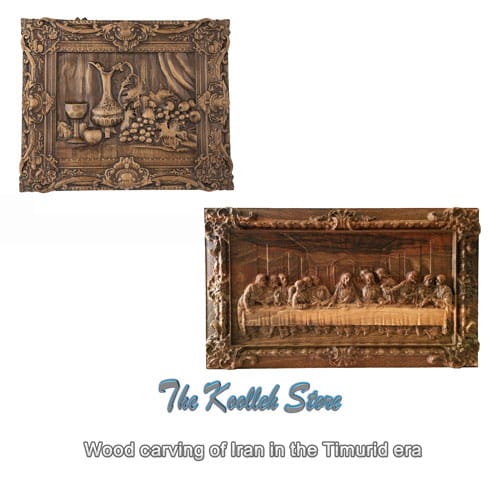

Wood carving of Iran in the Timurid era

In the second half of the eighth century AH, in the year 772 AH (749 CE), Iran once again became the site of invasions and destructions by a ruthless and bloodthirsty Mongol. In this devastation, many people were massacred and looted, and many magnificent buildings were razed to the ground. Of course, with all these interpretations, Timur’s destruction did not reach Genghis Khan, and in his attacks on different parts of Iran, Timur gathered artists and sent them to his capital, Samarkand. Fortunately, Timur’s successors also supported art and artists, so Iranian art gained another glory in the Timurid era. In the northeast of Iran, that is, in the legendary land of Turan, the decoration of the building was of special importance and its influence on the tomb of Amir Ismail Samani is well visible.

Azin was sometimes so important that it replaced the shape of a building. However, these ornaments had a special appeal and incorporated a set of all the principles of decoration, especially during the reign of Timur.

During the Timurid period, the art of woodcarving continued its past routine, and in some cases works with very valuable pavements remained. Very valuable examples of these works can be found in different places, especially Isfahan and Samarkand. The entrances to the tomb of the Shiite prophet Nabi in 777 AH (754 CE) in Isfahan, on which the word Ali is inscribed four times in the manner of the death of the Metropolitan Museum, are interesting. The decorations on Pataq at the entrance of the tomb of Shah Ismail in Isfahan, by repeating the word of God five times with these works, have a remarkable proportion and have a similar idea and design.

Two other examples of inlaid works of this period are the doors of Khajeh Azad Yasavi Mosque in Turkestan, one of which dates to 779 AH (756 solar) and the other to 797 AH (773 solar). The decorations on these doors include Islamic and Khatai designs, which are very similar to the wooden steps in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The inlaid works of this period have very beautiful and praiseworthy pavements.

Another valuable work of Iranian engraving is the tomb of Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili. This work, which is made with the method of tying knots and logs and the sharp role of Deh, is made and decorated with decorative and beautiful motifs of Khatai in the method of inlaid on logs of pear knots, which is praiseworthy. The inscription of the third line executed on this box shows the name of Sadr al-Din Musa, the son of Sheikh Safi, who represents its founder and about the year of construction, that is, the second half of the eighth century AH.

Manouchehr Sotoudeh writes about the inlaid wooden coffin of Taher and Motahar tombs in the village of Hezar Khal, Kojoor, which is another valuable work of this period: although it is four hundred and sixty-three years old [from about 804 AH] that this fund It’s here, but it’s still in its infancy.

There are no flaws in it, but it’s like they’ve just prepared this box. Calligraphers, painters, and engravers have used industry in the fund to acknowledge any skilled craftsman in articulating such an industry and to speak the language of fairness to the craftsmen. The calligrapher of this fund was Mahmoud Ibn Najib Al-Rostamdari and its carpenter or woodcarver, Master Mohammad Ibn Hussein Najjar, known as Kia Kurdi.

In the first room of the tomb of the four kings, which is the tomb of four elders of Lahijan, there is an inlaid wooden box, the date of construction of which is the first of Jamadi al-Awal in the year 829 AH (805 AH). On the top edge of the box are inscriptions in very fine print without paving, and on the north body are Islamic and Khatai motifs with lines and inscriptions in three parts of the inlaid work; On the margins and text of the southern body, there are inscriptions that are associated with the patterns of tying the penis; Also on the second (inner) border, the finished motifs are engraved with relatively good pavements; The presence of fringe weaving margins and the creation of highs and lows in the work have added to its beauty, so that it can be said that this work is one of the works that show the progress of inlaid art in that era.

Other works related to Lahijan region include the tomb of Seyyed Ali Ghaznavi in Tajan village. This box, which is made in the form of knots with wooden pieces, has a special work and elegance, the date of its construction dates back to 871 AH (845 solar years) and was made and paid for by Master Mohammad Ibn Yadegar Ibn Haji, a traveler from Tabriz. In performing this work, they have used Indian, Islamic, and Khatai maps along with Quranic verses in Naskh script. In doing so, the skill and mastery of the artist are very tangible, so that it can be considered as another masterpiece of its time.

An important example of such works that has reached the west of the earth is the shrine fund signed by two masters named Ahmad Najjar and Hassan Ibn Hussein. According to Professor Wiet, this fund was built by Amir Gostham in Ramadan 877 AH (March 851 AH) in Mazandaran province.

The inscription, which is the most important role in the fund and has always been a requirement of any building and religious monument during the centuries, has the same details as the decorations of that time and shows the originality and taste of the inlaid artist. In this inscription, the deep lines show the distances well, and the marginal stripes on both sides and at the bottom show different designs. Although these designs may be used in the role of carpet, gilding and plastering, they have not been seen in such works. The simple cross in one of the houses on the outskirts of Kandahar does not have a Christian aspect, but is an old symbol that can be seen in many religious monuments such as mosques and tombs in this land.